Parallel & Chiastic Stories in the Gospel of Luke & the Acts of the Apostles

Like reading any two-volume work by the same author, it is wisest to read Acts while paying close attention to Luke’s companion Gospel. They are paired volumes and if read separately, without reference to one another, the reader risks missing or distorting what the author intended. At best, it would be like seeing with one eye shut, losing focus and depth of field. Acts and Luke must be seen together to get the full picture.

More Than Chronological Accounts

Most of us read through Luke and Acts in sequence–beginning to end–following their stories in the chronological, linear order they were written. When read that way, the stories unfold roughly like this:

Gospel of Luke

Begin John & Jesus births, earthly ministry, arrested, trial, crucifixion, burial, resurrection, ascension End

Book of Acts

Begin Ascension, Holy Sp, Peter witnesses, Stephen dies, Paul saved, mission journeys, arrested, in Rome End

Chronology matters, of course, because Luke is intentionally writing an accurate historical account of all that he and other witnesses saw and heard during the period covered from Jesus’s life to the early church. His intent in is unambiguous in the opening verses of his Gospel . . .

“Inasmuch as many have undertaken to compile a narrative of the things that have been accomplished among us, just as those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers of the word have delivered them to us, it seemed good to me also, having followed all things closely for some time past, to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, that you may have certainty concerning the things you have been taught.

Luke 1:1–4

Luke intend to construct a carefully, accurately crafted narrative of all the things that happened concerning Christ and the birth of the Church. But Luke and Acts are not mere chronologies.

- Sidenote: One could just as easily focus the stories of Luke and Acts (or Scripture itself) according to their geographic sequences and cycles (after all Jesus “set his face to go to Jerusalem,” which means “the pillar or foundation of the God of peace”), going from Jerusalem to Judea and Samaria, or from Antioch to Asia, Macedonia, and Illyria, etc. We Modern (or Postmodern) Westerners are part of a clock/time-oriented, and task-oriented culture, and we must be careful not to see the Scriptures through those cultural lens primarily or alone.

Many students of the Bible over the centuries have recognized the manifold patterns and similarities found across the two books. It is evident to most that Luke wanted us to see his stories as more than mere chronologies. Luke wanted us to see how the apostles and the early church were similar to Christ and what He experienced. After all, Luke himself quoted Jesus who said, “Everyone when he is fully trained will be like his teacher” (Luke 6:40). So we shouldn’t be surprised that the Church and Christ’s apostles are presented in Acts in ways that reflect their similarities to the life and experiences of their Teacher found in Luke’s Gospel account.

The early church fathers recognized these similarities and patterns (types) in Luke-Acts and throughout the Scriptures. For example, Cyril of Jerusalem (A.D. 315-386), Bishop of Jerusalem (350-386), identified the similarities between Jesus’s baptism in Luke and the descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost in Acts this way:

John says, “I indeed baptize you with water, for repentance. But he who is coming after me, he will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and with fire.” Why fire? Because the descent of the Holy Spirit was in fiery tongues. Concerning this the Lord says with joy, “I have come to cast fire upon the earth and how I wish that it would be kindled.”

Cyril of jerusalem (A.D. 315-386), catechetical lectures, 17.8

Luke clearly intended, by the way he “compiled his narrative” and structured his “orderly account,” for his readers to see such connections and relationships between the characters, the symbols, and the types highlighted in the stories he was retelling. He had an almost infinite number of details he could have chosen to describe Christ’s life and ministry and the emergence of the early church, but he chose these details and not others, and he highlighted them in similar enough ways in both accounts that we would notice.

If we miss those similarities, connections, and relationships Luke included in both of his books, we will miss important aspects of the Gospel-Acts story. Worse, we may misunderstand Christ and the early church by missing them. That is a risk not worth taking.

Many in our age will have some real discomfort with the notion that the presentation of Jesus could be influenced by earlier models. Yet this concern seems allied to expectations that the “new” more purely represents the true . . . . Certainly, the idea of imitation generates concern that the very integrity of Christ is rattled if his presentation is modeled or shaped after previous models. But asking to read these narratives on their own terms means reading in light of the conventions of their own day; conventions that thrived on re-presentation of an ideal; in short, upon imitation. The presentation of the literary Jesus as a composite of archetypes, far from being an erosion of his character, would have appealed to Luke and to his audience as quite the opposite.

victor wilson, divine symmetries (1997), p. 192

Parallels between Luke and Acts

The sheer number of similarities, patterns, connections, and relationships found between Luke and Acts suggests they are not random, but intentional and even foundational to both books. They, in fact, may establish a larger framework for both books.

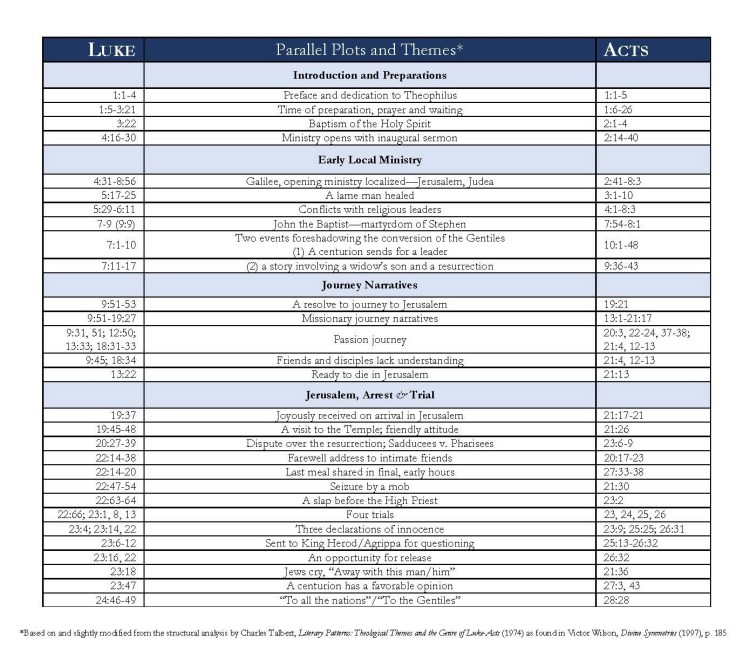

Charles Talbert (1974) identified at least one such framework based on the thematic and plot parallels in both the Gospel and Acts.

Chiastic Structures within and between Luke and Acts

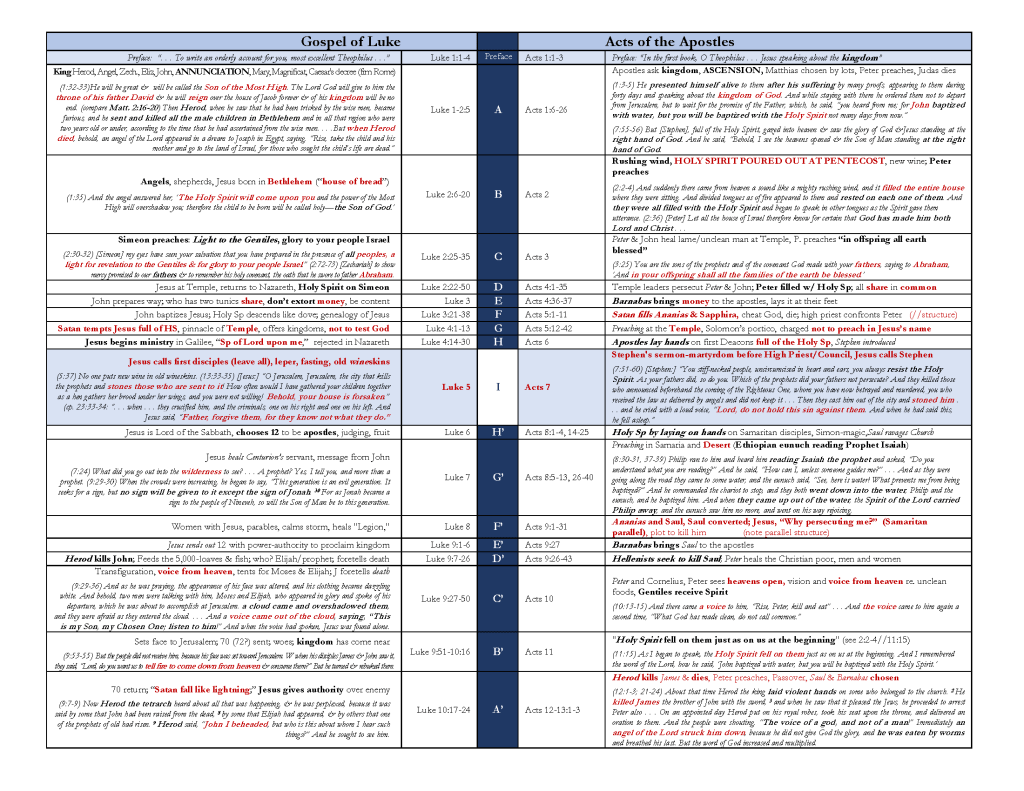

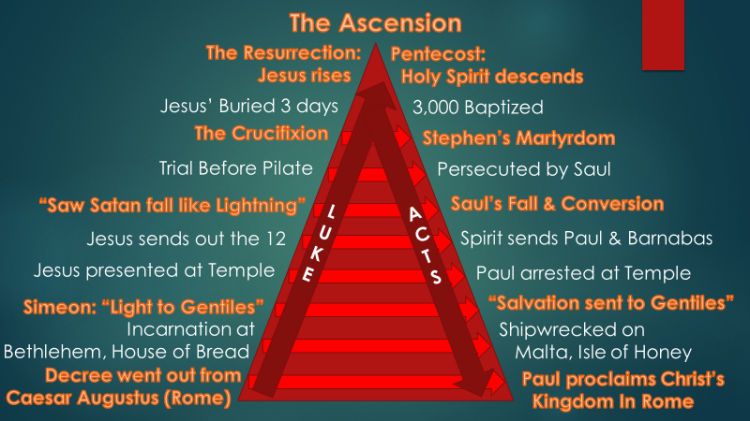

The parallelisms (A-B//A’-B’) between Luke and Acts are quite obvious, but they are not the only structures that Luke has included in his two books. Chiasms (A-B//B’-A’) are also evident throughout Luke and Acts. Here is an example from the first halves of the two books. They are in parallel order (each beginning with chapter 1), but each half has a discernible chiastic structure within its book two and with the other book.

Each of the inclusios or bookends of the first halves of both books deal with kings/kingdom, Herod and/or death.

Luke A: Jesus will receive the throne of his father David; King Herod sought to kill Jesus (and 2-year-olds ).

Luke A’: Jesus sees Satan fall like lightning; Herod the Tetrarch kills John

Acts A: Jesus ascends to throne (Stephen sees at God’s right hand); speaks about the kingdom and Holy Spirit

Acts A’: Herod kills James and an angel strikes down Herod and he dies because he pretended to be a god

The chiastic centers of the first halves of the two books highlight the transition from Old Covenant to New

Luke I: “no one puts new wine in old wine skins”

Acts I: “you have betrayed and murdered the Righteous One”–but sees him seated at the right hand of God).

Chiasms in the First Half of the Two Books in Parallel

Chiasms in Luke-Acts, Hinged at Ascension (not in Parallel)

Recommended Readings

David A. Dorsey, The Literary Structure of the Old Testament: A Commentary on Genesis-Malachi (Baker Academic, 1999)

James B. Jordan, Through New Eyes: Developing a Biblical View of the World (Wipf and Stock Publishers, 1999)

Peter J. Leithart, A House for My Name: A Survey of the Old Testament (Canon Press, 2000)

Victor M. Wilson, Divine Symmetries: The Art of Biblical Rhetoric (1997)

“Recovering the Old Testament as a text in which Christians live and move and have their being is one of the most urgent tasks before the church. Reading the Reformers is good and right. Christian political activism has its place. Even at their best, however, these can only bruise the heel of a world that has abandoned God. But the Bible–the Bible is a sword to divide joints from marrow, a weapon to crush the head.”

Peter Leithart, The Kingdom and the Power

You must be logged in to post a comment.