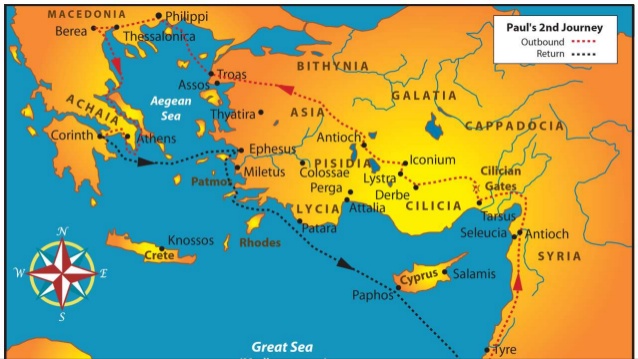

Following the Via Egnatia, the Roman road between Byzantium (later Constantinople) and the Adriatic Sea (ending at modern city of Durres, Albania), Paul, Silas, and Timothy arrived in Thessaloniki (17:1-9) from Philippi (about 100 miles). The gospel was received well, but turmoil followed. Some of the new believers there later lose their lives (I Thess. 4:13). Departing Thessaloniki, they leave the Via Egnatia and head southwest toward Athens, stopping en route in Berea (17:10-15). In Athens, “a city full of idols” (17:16), Paul preaches at the synagogue, the agora, and then to the local philosophers and civic leaders at the Areopagus (17:17-34).

Raphael (1515; Royal Collection of the United Kingdom)

Acts 17: Paul comes to the cultural heart of the classical world–Athens–centered between Jerusalem and Rome

Acts 17 recounts Paul’s second missionary travels across southern Macedonia to the ancient capital of the Greek world. Located between Jerusalem, the city of David and the liturgical heart of the Jewish nation, and Rome, the political power center of the Roman Empire, Athens was the symbolic heart of the Hellenistic culture of the Roman Empire. The Greek gods, recast as Roman gods, and the idols of mind and marble, emanated from this heart of Hellenism. Paul’s visit to this cultural significant center is recognized structurally in Luke’s account as the center of his missionary labors between the two extreme poles of his ministry: Jerusalem and Rome.

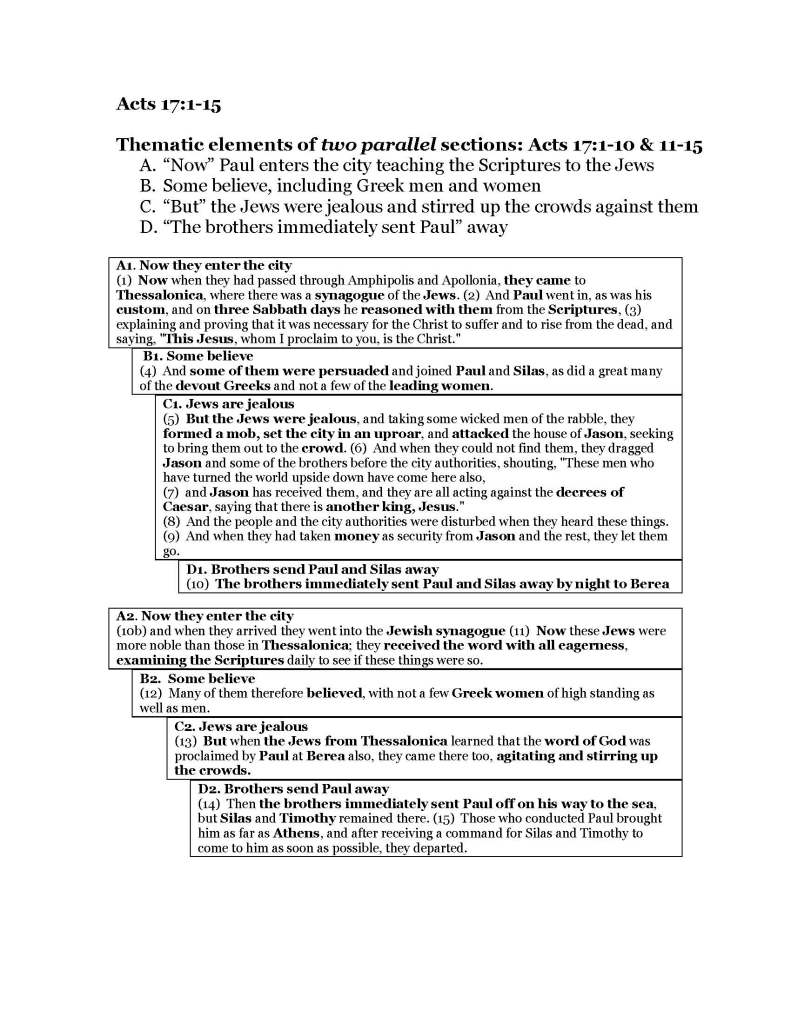

Thessaloniki and Berea: Cities in Parallel

The first 15 verses of Acts 17 describe Paul, Silas, and Timothy’s arrival in Thessaloniki and Berea. Luke’s descriptions of their work in these two cities are told in parallel construction.

On this small hill located just below the Acropolis and Parthenon in central Athens, the Apostle Paul

preached to the Greek philosophers (Stoics and Epicureans) and civic leaders of his day. The Romans

imposed a new government on Athens in the first century. The hall once located there served as the new

government center. It also hosted philosophical and civic lectures and debates.

Athens and Paul’s Preaching at the Areopagus

Notes

17:16: Paul faced angry mobs in Thessaloniki and Berea, but he comes to Athens he is angry and stirred up in spirit against the pagan idolatry pervasive in the city. The religious core of Hellenistic culture is paganism and idolatry. That revolts him. Extrabiblical sources like Livy’s History of Rome and Pausanius’s Description of Greece mention the vast number of idols found in Athens.

17:17: “Reasoning” may be better translated “debating” (dialegomai–associated with Socrates’ famous dialogical method of teaching). The link between idolatry and conflict is evident. For a culture that prided itself on its reason and beauty, a deeper look revealed irrationalism (arbitrary gods) and sexually violence and moral bankruptcy.

17:18: Paul is insulted by the arrogant Stoics and Epicureans as a “babbler” for introducing the idea of Jesus’ resurrection from the dead—some foreign (Jewish/Christian) gods. Luke returns the insult (v. 21) when he says the Athenians “spend their time in nothing except telling or hearing something new.” The obsession with “the new” is an idol of contemporary American consumer culture.

17:22: Paul also mocks them not-so-subtly by saying that “in every way you are very religious.” Then he points out the obvious: idols everywhere, even “To the unknown god.” He then schools them on what they do not know.

17:24-25: The heart of this section is his declaration that “the God who made the world and everything in it, being Lord of heaven and earth, does not live in temples made by man, nor is he served by human hands, as though he needed anything, since he himself gives to all mankind life and breath and everything.” This statement echoes Stephen’s sermon in Acts 7:48-50 and Solomon’s temple dedication in I Kings 8.

17:26-29: Rhetorically, Paul turns the tables on the philosophers by demonstrating that what they don’t know, he knows, and moreover, he knows their own poets and theology. He summarizes the biblical creation story and then quotes Epimenides of Crete, “In him we live and move and have our being.” The poet has recognized a biblical truth that Paul is not afraid to affirm. He upholds and sustains us. The Greek and Roman idols don’t do that. And then he quotes from Aratus’s poem (“as one of your own poets has said”) “Phainomena,” “For we are indeed his offspring.” So he reasons that if we are God’s offspring, then the divine being is not like gold or silver or stone or any silly idol dream up by human ingenuity.

17:30: He then drives home the point that idolatry is ignorance (another insult) and that God commands everyone to repent. For he will judge the world righteously, not capriciously, according to Christ who was appointed to this task by his resurrection from the dead.

17:32: Some were convinced and believed, others mocked. Some wanted to hear more of what he had to say.

Overall, Paul’s rebuke of idols and affirmation of the Lordship of Jesus and his resurrection from the dead are strong statements, rhetorically powerful and winsome, and persuasive for all but the hardest of hearts in the heart of the cultural capital of idols.

Recommended Readings

Clinton Arnold, Acts (Zondervan, 2002)

David A. Dorsey, The Literary Structure of the Old Testament: A Commentary on Genesis-Malachi (Baker Academic, 1999)

Luke Timothy Johnson, The Acts of the Apostles (Sacra Pagina, Liturgical Press, 1992)

James B. Jordan, Through New Eyes: Developing a Biblical View of the World (Wipf and Stock Publishers, 1999)

Peter J. Leithart, A House for My Name: A Survey of the Old Testament (Canon Press, 2000)

Victor M. Wilson, Divine Symmetries: The Art of Biblical Rhetoric (1997)

“Recovering the Old Testament as a text in which Christians live and move and have their being is one of the most urgent tasks before the church. Reading the Reformers is good and right. Christian political activism has its place. Even at their best, however, these can only bruise the heel of a world that has abandoned God. But the Bible–the Bible is a sword to divide joints from marrow, a weapon to crush the head.”

Peter Leithart, The Kingdom and the Power

You must be logged in to post a comment.